Yes, I am writing this in light of some unnamed event, which has no bearing on my future whatsoever, and no, I’m not constantly refreshing my laptop waiting for emails with confetti to come in. However, I figured this was a great time to talk about one of my favorite philosophers ever. Go grab some popcorn, clear your mind a little, and ready your eyes for the most confusing analysis of the human condition I could find in good faith.

For a long while I have lived with the notion that I was the most normal being that ever existed. This notion gave me the taste, even the passion for being unproductive: what was the use of being prized in a world inhabited by madmen, a world mired in mania and stupidity?

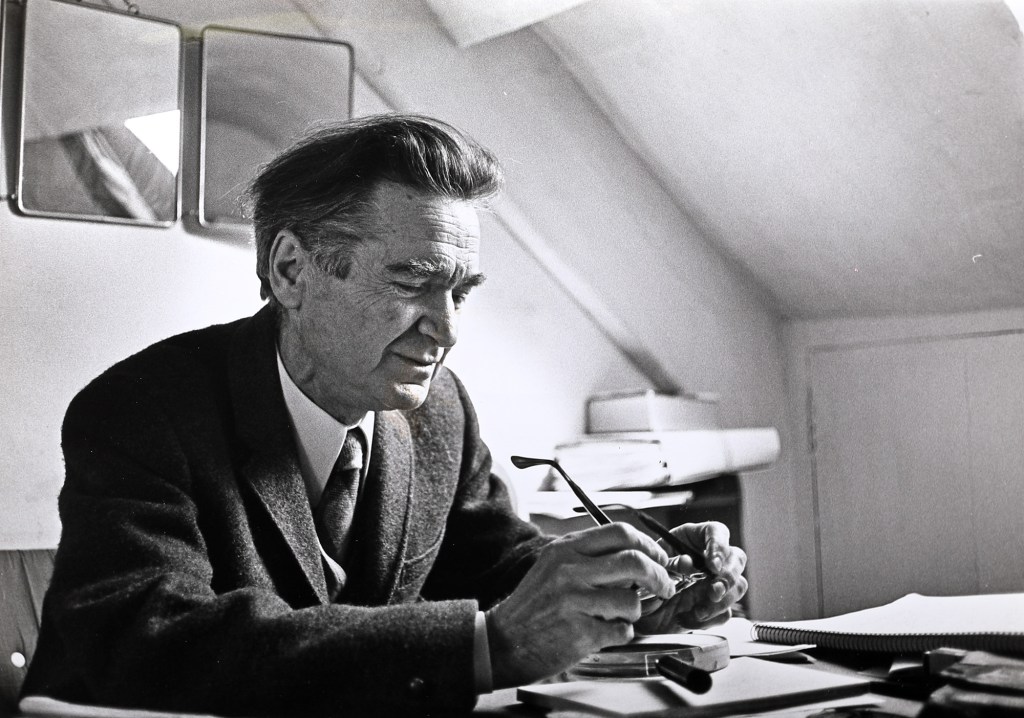

Emil Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

Emil Cioran was a bit of an odd fella. His hair looks like something you’d find in a really bad 80’s period film, and his writing stumbles between “I really hate insomnia” and “this chestnut that just fell from a tree makes me feel alive”. He wrote a lot, a lot, simply because he liked writing. And all of this, to him, seemed completely normal. Cioran was an absurdist: he believed everything and nothing made sense, and he found ways to live with this reality by doing whatever he wanted.

Cioran was very interested in one specific aspect of absurdism: how it interacts with people. At what point the unstoppable force of “nothing makes sense” meets the immovable object of “we have to die at some point”, which is the subject of this terrifyingly long (I know) blog post.

Now it may not come as a huge surprise, given how little regard philosophers have for what is societally regarded as “acceptable”, that Cioran thought death was the ultimate success. “Say what we will, death is the best thing nature has found to please everyone,” he says. “What an advantage, what an abuse! Without the least effort on our part, we own the universe, we drag it into our own disappearance.”

What might be surprising, though, is what he follows it with:

No doubt about it, dying is immoral.

What! Was he not just speaking about how beautiful it is to die? How much of a success it is? No, you bumbling buffoon! You complete jester! You see, Cioran was also the proud owner of a really odd belief: failure is, in every case, better than success. In this case, death may be a success, but it is better to fail at dying. Similarly, it may bring you a lot of money to start a successful baguette shop–but what would it bring you to fail? It would bring you experience, fresh ideas, a story to tell, and maybe even a big change in your perspective.

This is what Cioran preached; “[t]o have failed in everything, always, out of a love of discouragement.” He lived his life himself failing as often as possible, because he simply found it far more interesting. Stephen West, from Philosophize This!, puts it like this: say you’re at a high school reunion. Who would you rather talk to: the guy who owns a succesful business and is happily married with three whole kids; or the guy who tried engineering, and failed, and wandered around in Germany until they found blue-collar industrial work, where they also failed miserably, followed by becoming a yoga instructor, without any idea of how to do yoga!? In short, “failure builds character”.

Let’s take a quick look at the modern world! Celebrities, by all accounts, are pretty boring individuals. They are famous because they have learned, in one way or another, to become fairly asinine: personality must be set aside for the sake of broad appeal (except in the case of reality TV, which Cioran I assure you would love). We harbor a lot more love for people like our friends and family than we do for people like the President, simply because we don’t see the President burn his toast on accident or spill orange juice on his expensive suit. Love, in this way, is not just related to failure–it is based on failure. We love the people we see fail, because that makes them people.

I’m sure you’ve heard the phrase “nobody’s perfect” a million times. Cioran is not interested in this kind of positivity. Indeed, Cioran doesn’t care whether failure is necessary, he cares about whether we should want it. And, he argues, we should! So if you, too, are waiting on EA/ED decisions this hellish week, remind yourself as I do me: an acceptance is good, but a rejection is better. And a deferral, of course, means they liked your application so much they want to read it again.

See ya, and good fucking luck.

Note: Based loosely on Episode 156 of Philosophize This! Please go listen to it. God knows I have myself. Many times.

Leave a reply to Verona Tovagliari Cancel reply